Italiano Deutsch Indonesia |

Historical outline of

a Sardinian village in strong expansion: |

Sardu Russian |

by Emanuele Atzori

![]()

Capoterra is one of the Sardinian town councils that, in the last 10 years,

had one of the highest population increases in the island and a considerable

transformation of town planning. Now it is identified by a set of inhabited settlements

distributed in three different localities, about five kilometers apart. The first urban

site, the oldest one, was developed from a seventeenth-century village and lies at the

foot of the hills of Montarbu, Punta Sa Loriga and Mount Arrubiu. The second was started

in the early 60s in the coastal strip that runs from Maddalena as far as Cala d'Orri; the

third village took form in 1966, in the lower-hilled area of Sa Birdiera and Pauliara, at

the foot of Mount Santa Barbara. An outline of the historical and economical changes that

characterized this village since its foundation in 1655 until the present day is planned

to be included in the book published by Carlo Delfino from Sassari, with the title "Capoterra,

da baronia feudale a periferia urbana" ("Capoterra, from feudal barony to

urban outskirt").

This article will be a quick analysis of the themes widely treated in the

volume that interested readers can obtain from Delfino Editore, Via Rolando 9/A, 07100

Sassari (Italy).

It's not possible to mention the present Capoterra without hinting at the

first human settlements in the area. Villages formed by huts possibly derived from the

Ozieri Culture (recent Neolithic), laid by Cuccuru de Ibba (the prehistoric lithic

workshop studied by Enrico Atzeni) and by Pranedda de Punta Sa Loriga. Tracks of some nuraghe

are visible at Carrubba Durci, Is Antiogus, Is Cuccureddus.

Punic structures were found at Su Loi, in the hill channel of S. Antonio

and in other mountain areas.

S. Efisio parish church

Since the second century before Christ human settlements

became numerous. In fact, when Sardinia became the granary of Rome, little agricultural

centers rose in Capoterra, scattered throughout the whole territory. The biggest one lay

beside the pond, probably near Tanca Sa Turri. It was the one from which the ancient

"Villa di Caput terrae" originated, mentioned by a giudicale

charter of 1107. But it wasn't the only inhabited nucleus; others arose at Perda Su Gattu,

Maddalena, Sa Cresiedda, Birdiera, Baccalamantza, Su Lillu, along the Channel of Liori

(Via Deledda) and the Channel of S'Acqua e Tomasu. We are peplexed, however, examining the

large number of archeological mountain sites. Who lived there? There are several

hypothesis. Maybe it was people from the Phoenician culture who were opposed to the

excessive power of the Romans (therefore they were rebels who hid in the mountains), or

they were Mauri deported to Sardinia. Perhaps more simply they were a family

nucleus, coming from the punic coastal area, who lived from sheep-farming and sheaf

cutters supplying the nearby cities of Nora and Karales.

We know the names of the head of the family of the little village that was

the medieval Capoterra, because they were reported in a giudicale chart of the 1108: five

surnames in all (Pizia, Pira, Corsa, Foco and Albuo), that have nothing to do with the

actual familiar clans.

Capoterra was part of the Curatoria of Nora, and with the decline of this

town it became the chief town of the Curatoria, giving rise to the historical region just

called "Caputerra", that extended from the Cagliari Pond as far as Capo

Pula.

When, in 1258, the Giudicato of Cagliari was divided, the Curatoria passed

to the Donoratico. But after a short time they, who belonged to the little group of the

"Lord of Sardinia", lost the village of Capoterra, keeping Santa Maria Maddalena

and all the other existing settlements, some of which no longer exixt. Capoterra, in fact,

passed into the control of Mariano II of Arborea (faithful ally of the Pisans), who

conceded it to Giacomo Villani. Between 1292 and 1293, during the hostilities among Pisans

and Genoans, Capoterra was put to the sword by the soldiers of a Genoan fleet that docked

at Maddalena. In some sources we read that "its towers were destroyed (but who

knows where they were) and all the harvest was burned". When Mariano died, Pisa

claimed the possession and expelled Villani. It was so that, on February 1324, Pisa chose

the little harbour of Maddalena to disembark its troops that had to stop the military

conquest action undertaken by the Aragon army of Prince Alfonso. As it is well-known, the

defeat of Lutocisterna, near Elmas, marked the end of the hegemonic hopes of Pisa. Alfonso

of Aragon gave Capoterra back to Giacomo Villani, whose son sold it again to the Arborea

family, or better to Timbora di Roccaberti, mother of the famous Eleonor. When relations

between the Giudicato of Arborea and the Kingdom of Aragon were based on conflict,

Capoterra paid the penalty, because it was destroyed again; this time by the Aragon

soldiers commanded by Berengario Carroz.

For the ancient "villa" it was the end, because its

country remained almost depopulated for three centuries, so that Fara spoke about a region

"tota deserta et sylvosa". Maybe, the only people were the hermits of

the St. Barbara Church, built in 1281, in Romanesque-Pisan

style, with Arab decorative influences, by Gallo, the archbishop of Cagliari. The church

was built as a hermitage known since the High Middle Ages, when it was seat of the

basilian monks.

It's not useful to mention the transfers of ownership of the uninhabitated

village. I only recall that, in 1494, the territories of Capoterra and Sarroch were bought

by a doctor, Ansia Torrella, who created the so-called Baronia of Capoterra and Sarroch.

Jumping several feudal passages, we arrive at the baron Girolamo Torrellas who, on May 9th

1655, founded the actual village, calling it "Villa di S. Efisio". So

he built a palace in the form of a castle and a church dedicated to S. Efisio. These

buildings were located where we can now find the Principe di Piemonte nursery-school.

At the beginning of the 17th century, the land of Capoterra saw the arrival

of new monks who were looking for quiet places to pray. In 1615 the Girolamiti friars

built the country church of S. Girolamo, that then became seat

of the presbitery, suppressed in 1867. The Minor Conventuali friars took possession,

around 1640, of the St. Barbara temple, giving up to the archbishop of Cagliari the

beautiful church of S. Maria di Uta that was no longer suitable for meditation and prayer.

Procession of S.Efisio in the streets of the village

When even the Fancescani friars had to leave St. Barbara

because of the law for the withdrawal of ecclestical goods (1867), the temple became state

property and the supervision of the traditional feast of St. Barbara (that now is held on

the first week of July) was held at the parish church of S. Efisio.

It's unnecessary to mention the problems that the little community of

Capoterra had to face until the liberation from the bonds of feudalism that, in Sardinia,

was repealed in 1838 by Carlo Alberto. We can only say that this community had the

misfortune to have barons and baronesses who never loved their vassals and didn't lift a

finger to improve existing structures, only demanding many taxes to which the inhabitants

were submitted: "Laor di corte", that concerned who sowed using with

oxen and plough; the several royalties that had to be paid in kind or in money,

"chancery royalty", that concerned the persons who had come of age, "feudal

royalty", that concerned everybody, "hen royalty", that concerned married

men, "kid and cheese royalty", "wood, estate, straw, honey, lard,

slaughtering, tavern and guild royalties"; and the various "deghini",

that were taxes with an expiration arranged in advance for shepherds and pigsties. The

last feudal baron was Lorenzo Zapata, son of Efisio. It was a wide feud, that extended

from Capoterra and Sarroch, even to Las Plassas, Barumini and Villanovafranca. Its ransom

was sanctioned with royal charter on May 9th 1840.

With the repeal of the feudal system, there began a big economic change in

the village (common to most of the Sardinian villages). In the township, then with little

more than 800 inhabitants, there was the alienation of the wide lands of the feud that

were used collectively by the vassals (in other words they were entrusted in rotation to

the various farmers while a bigger part was left for free pasture). To boost agriculture,

the Piedmontese Governament divided these community lands into lots of about two hectares

and granted one lot to every head of the family, helping the persons with no property and

the little owners. In this way every farmer of Capoterra began as a landowner, but with

the duty to enclose his plot, cultivate it and (unfortunately) to pay the land tax that

was established few years later.

All this provoked the hostility of the rich landowners, who were great

livestock breeders (cows, goats, sheep) who hadn't accepted the measures that repealed the

community pastures. So, Capoterra was one of the few villages in the island where it was

necessary to intervene with a handful of cavalry of Sardinia to quell the abuses of power

of the breeders against the "new farmers".

With the sunset of feudalism, even the 16th century church built to

Gerolamo Torrellas' will in 1665 fell into ruins. The need arose for a new church, more

adequate to the demands of the village. The realization of this temple, projected by

engineer Francesco Immeroni, started in 1855 and ended in 1858. The huge costs for a poor

community as Capoterra was then, were supported by the town council with a loan of 20.000

lires handed out by the Loan and Deposit Fund (Cassa Depositi e Prestiti).

|

|

The richest families who lived in the village soon

understood the need to control everything, seeing that the high social classes had more

and more room. Here is the reason why the mayors of the second half of the 17th century

and of the period preceding the birth of the Italian Republic, were always elected by the

wishes of the hegemonic class, that of the breeders and landowners. The agriculture boom

wanted by the government had its consequences, with a substantial decrease of bred

livestock, even if in this town council the mountains continued for a long time to provide

adequate space for goats, pigs, sheep and cows (which went downhill during the summer). A

great impulse came from the new agricultural models, introduced by the marquis Stefano

Manca di Villahermosa in his firms of Villa d'Orri and Tanca di Nissa. It's probable that

certain cultural techniques were learned by the Capoterran farmers just working in these

structures that were a model for those times.

In 1860, the opening of the S. Leone mine by a company from Paris, the Petin

Gaudet, owner of the complex "Compagnia degli Alti Forni e Acciaierie della

Marina e delle Macchine a Vapore" ("Company of the furnaces and steelworks

of the Navy and of the steam machines"), allowed the inhabitants of Capoterra to

attend, maybe first in Sardinia, at the amazing innovations of the Industrial Revolution,

that had started in England at the beginning of the previuos century. Some Capoterrans

adapted to work in the new mining complex, being first labourers, then miners.

This mine, which towards the end of the past century was sold, staying idle

for various periods until its closure in 1963, deeply marked the economy of this village.

The extraction work (even if hard and full health dangers) gave the chance for many

families to cross the difficult economic situation at the beginning of this century, when

this village was still geographically isolated, far from the main communication routes.

The relative closeness to Cagliari was off-set by the lack of means of public transport of

those times and, sometimes, no use at all, when the bridges of Scafa collapsed for various

reasons.

In the 20s the opening of the saltworks of Macchiareddu assumed great

importance for the poor economy of the village. It was, however, a seasonal job, in which

the workers' exploitation was well stage-managed because it was founded on the piecework

and on the ruthless competition among the teams of salt collectors. The boost given to

agriculture in the fascist period was cancelled out by the deleterious effects of the war

and the recovery was not easy.

To make up for this, some trader in the postwar years brought back a

traditional pratice, bird-catching, that had been used in the past in difficult times.

With the closing of the S. Leone mine, to tackle the heavy employment problems of the

area, bird-catching was even disciplined with a regional law, with the support of the

political parties of the left. Today it is forbidden.

The arrival of the petrochemical industry at Sarroch and Macchiareddu

inflamed again the hopes of recovery, but for many years the Capoterrans had to be content

with entering the factory with the contractor firms, without a safety agreement and with

reduced salaries, for the lack of an adequate specialization and because the Employment

Agencies of Assemini and Sarroch favoured unemployed persons. Certainly however, in the

70s, the new industrial settlements contributed to remarkably modify the economic and

social realities of this community, with a considerable reorganisation of traditional

"full-field" agriculture and the beginning of new techniques of greenhouse

cultivation.

Since 1951 until today, Capoterra has changed in a radical way. In these 45

years there has been social and economic transformations so deep that several studies of

demographic problems have been taken aback. The growth of the number of inhabitants has

been strong, reaching at the end of the month of December 1995, 18,350. The growth, begun

in 1961 (6,355 inhabitants), continued in 1971 (8,028 inhabitants) and had a considerable

leap forward in 1981 (12,208 inhabitants) and in 1991 (16,428 inhabitants). Since 1951

until today, the percentage variation of the demographic increase has been 34,6 % more,

one of the highest in the island, second only at Quartu in the Cagliari district.

The reasons of this powerful growth are known: the strong immigration of

people from Cagliari and other nearby towns who chose Capoterra as a place of residence.

Everything started with the birth of the first residential villages, in the

second half of the 60s, first in the coastal area and then in the hills of

Birdiera-Pauliara. The reasons that induced so many families to move in the territory of

this village are several: for some it has been a real escape from the town, which have

become less pleasant because of the traffic, incessant even in the night, and for the lack

of adequate green places; for others it represented the chance to live in a house

surrounded by a garden, lit up by the sun every hour of the day, near a hill or the sea.

Finally, for some people it was only a property investment for gain. In its favour it had

as predominant importance the fact that the new residential villages are relatively close

to the town and the Macchiareddu and Sarroch industrial areas, where generally it's easier

to find a job. Even the undeniable beauty of the land encouraged this choice. In actual

fact it is still a model for new entreprenurial initiatives that aim at the realization of

other residential villages, whether along the coast or near the hill.

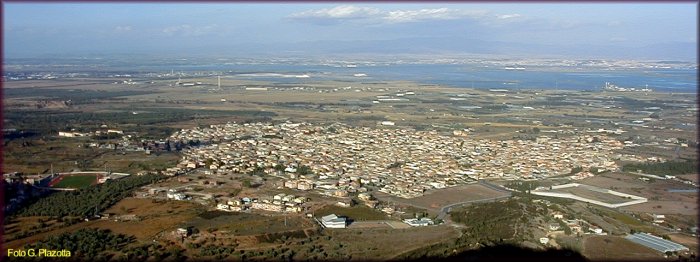

View of Capoterra

Today, therefore, the town council of Capoterra can be defined an urban

centre with a polymorph expansion (leopard-patched) and very heterogeneous in its human

composition. The following figures are sufficent to give an accurate idea of the

distribution of population in the territory: by now only about 60% of the population live

in the main village built in the seventeenth century, about 28 % live in Maddalena and

Torre degli Ulivi; about 12 % in the Poggio dei Pini area.

In a situation like this, every new village becomes an independent entity,

released from the typical tradition of the Capoterra of the past. But even in the village

the changes are deep and draw their origins from the changed living conditions. The

arrival of industry, in the 60s, caused the first sensible productive and employment

change in the area. The great farms ceased to exist and became land to divide into plots.

The full-field cultivations were reduced and many vineyards were uprooted, even because of

the subsidy of the Sardinian Region that was handed out for that purpose. Today the

profitable agricultures practised in the area are essentially the greenhouses, but they

are threatened by the problem of the saline water wells (a non-existent problem in the

past, because around Capoterra it was possible to find fresh water springs even in fields

near the pond).

To all of this we have to add the social discomfort that, for some time, is

gripping our island and, more generally, southern Italy. This is especially after the

failure of some industrial projects, essentially directed for gain on the regional and

state funds, handed out like a lolly scramble years ago without a development perspective.

(translated by Giorgio Plazzotta and Jenny Setchell)

![]()